Lately I have been mulling over a number of things related to the Gulf of Mexico that I’ve seen since I first started diving off the west coast of Florida in 1992. Waiting to head out the mouth of the Aucilla to dive off the Econfina a couple days before Thanksgiving probably made me a little nostalgic about when I got to work in this area on Michael Faught’s project in the early 1990s. I thought I would talk about some of the underwater archaeological work out there and then some connections between long term changes to the environment and impacts to biotic communities. The red tide today is a good example of the cumulative effect of all kinds of impacts.

A bit of a hodgepodge I admit but it will set the stage a little for issues I will eventually expand on in greater detail. It might be easiest to think of the landscape as one continual property from the Last Glacial Maximum until now. The obvious huge change is that from 22,000 years ago, until roughly 5,000 years ago a bit more that 50% of all Florida has been inundated with salt water. What we think of as Florida has only existed for a little less than 5,000. And it took the better part of 17,000 for Florida to turn out like it has.

I’ll break this up between some of what we know about the Pleistocene landscape, that is of course only seen in glimpses through the water column and the marine sands on top of it now, and some discussion of that briny marine world and changes I have noticed in the last 30 years. Because this process of sea level rise took so long there are some very important considerations we can address about how that rearranged all of the biotic communities.

I am not really sure how many total dives I have in the GOM, probably several hundred by now. I’ve got something like 2,000 logged dives spread out in too many different formats to sort them out easily. In addition to working on projects directed by several other researchers I spent most of my dive time working on our project locations well off the beaten path at sites between 40 and 130 feet deep from the Florida Middle Grounds and half a dozen places along the old Suwannee River channel.

I got to dive the widest range of GOM locations between 2008 and 2015 as part of the work that Jim Adovasio and I have been doing along the PaleoSuwannee River channel and a dozen other areas where we collected side scan sonar and sub-bottom profile data and then dove to ground truth and sample a handful of the 2,500 karst features we saw in the remote sensing imagery.

Principle Investigators deep in aah, consultation about Ziploc burst strength, I think. 2009

Side scan sonar creates a map of the seafloor surface and a sub-bottom profiler, as the name implies, generates an electronic profile showing the different layers of sediment and bedrock directly below the tow-fish you drag around behind the ship. Kind of like an electronic backhoe image. Here is a Youtube video from Edgetech showing one of their better combined tow-fish packages from a couple years ago to let you see some remote sensing imagery https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LRhN9zROsKI

The purpose of all the remote sensing and data gathering is to get a look at what the existing seafloor looks like with marine sands draped over Pleistocene sediments resting on ever older bedrock. Much of the Pleistocene land surface is eroded and gone. However, tucked within karst limestone features (sink holes, old recessed river channels, etc) there remains the possibility of finding preserved sequences of sediments that originally would have been land, freshwater river bottoms, brackish marine environments, and finally marine seafloor at the top. Expressing the modern to prehistoric sequence in four words a couple of years ago I titled a paper Salty, Brackish, Fresh, and Dry. In essence this is what happened to half of Florida.

As you may well expect the suite of plants and animals living at any one spot changes entirely through each stage of that sequence. One particularly interesting example of location, location, location, remaining important, even for different reasons, is that the denser limestone bedrock that erodes much more slowly than the surrounding soft limestone was typically dolomite and in several cases knappable chert that could have been made into stone tools. That exposed bedrock today serves as a solid substrate for marine organisms to live on, or in and under if there are holes or crevices. So it turns out that places along the old shore of the PaleoSuwannee River with good quality stone that would have drawn people in the Pleistocene are the favored habitat for Grouper today. If you know a good rocky Grouper spot, there is a sporting chance prehistoric people would have examined the stone for very different reasons long ago.

From an archaeological perspective then, with ample doses of geology, zoology/paleontology, and ecology, thrown in for good measure, we are looking at a Paleolandscape that was empty of people when the northern glaciers started to melt and sea level began to rise, again, circa 22,000 years ago. Some time prior to 14,600 years ago the first people arrived in Florida. This is my opinion based on early human occupation surfaces at Page/Ladson, Wakulla Springs, and Vero, which in my estimation have the strongest cases for dated human presences that early in Florida, though all of this is still quite debatable. At various times I have been PI, Co-PI, or Field Director, at all three so I know them pretty well and will get around to talking about all of them more in the future.

Along the shore and slightly inland you get the greatest range of available resources from the neighboring ecotones (marine and terrestrial in this case). This works for people and animals, and when combined with an understanding of the available freshwater being much lower at this time (essentially held above the salt water) you can see what a draw the nearshore areas would be to plants, animals, and at some point, humans. Geoscientists Faure, Walter, and Grant had an excellent article describing many aspects of this scenario in Global and Planetary Change #33 in 2002 titled: The Coastal Oasis: Ice Age springs on emerged continental shelves. Available here as a pdf: https://www.fandm.edu/uploads/files/12520708593016510-faure-et-al-2002-the-coastal-oasis-ice-age-springs-on-emerged-continental-shelves.pdf

At some point after sea level started to rise the animals and early human arrivals are being pushed inland and concentrated in a way that eventually makes them archaeologically visible- I.E. they should become dense enough on the landscape that we can detect them even 15,000 years later. The mastodons, mammoth, bison, sloths, and even humans are slowly but surely being herded inland. There are new dangers now too. If you go the wrong way (stay on high ground and get isolated or cut off) or loose contact with others, you can suffer a personal extinction pretty quickly. We are still essentially looking for needles in a haystack, but the haystack is only half the size it used to be.

Figuring out exactly when the landscape was covered is critically important to timing where the land was in relation to the first arrival of people (that we are aware of- sort of a minimum date really). The latest and best sea level curve to date was done in 2018 by Shawn Joy at FSU (his thesis is available here https://diginole.lib.fsu.edu/islandora/object/fsu%3A650288/

When the maximum amount of water was tied up in ice the sea level was 143m (~469ft) below today. For most of the west coast of Florida that is about 230km offshore, a bit less, maybe 200km offshore for most of the panhandle.

The process of filling up the Gulf with meltwater was akin to filling a very large bathtub with a bit of sloshing around in the middle and at the end of the whole thing and took about 16,000 years in total (on average rising about 1cm a year or 3.25 feet (1m) every century). That seems pretty slow but where it matters out on the flat Floridian Continental Shelf is the horizontal distance cover, per yearly average, works out to about 15 feet a year. During a steady period of sea water rise ten years after a campsite was used it could be 150 feet offshore.

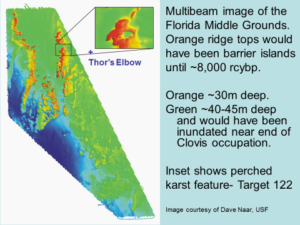

Keep in mind it was not a strictly steady rise for all 16,000 years. At various periods things rose faster or slower and for over 1,000 years temperatures were cooler and sea level would have dropped perhaps as much as 10m. The Younger Dryas cool period happened from about 12,800 to 11,700 years ago, depending on whose data you use, at a time critical to our story here. At the start of this period people had already been demonstrably in Florida for the better part of 2,000 years and some of the most interesting landscape features stayed dry land for an extra thousand years because of the cooling: the Florida Middle Grounds and an intersection of the PaleoSuwannee and another ancient river (a site we called Thor’s Elbow- plotted on the Multibeam image).

The slosh at the modern end of the Ice Age sea level rise began about 6,000 years ago when modern seashores were breached, water rose about another meter (3ft above todays shore) and slowly settled back to the modern shore about 4,500 years ago, give or take. All of the dates and sea level points are a bit mushy but in round numbers they are pretty close.

Slowly but surely I am coming around to things that would have been interesting landscape features during the Pleistocene to early humans and the exotic beasts around them, and now today are very important marine life sanctuaries (in the case of the FMG’s at least).

After identifying some very interesting features in the Middle Grounds we got to dive a few locations between about 85 and 120 feet on the eastern ridge. Dave Naar at USF gave us a huge version of the Multibeam Side Scan Sonar image below before we went out so we picked what we thought might have been a good sized lake on top of an island as late as even 8,000 years ago to dive. We dove inside what we decided to call “the Eye of Osiris” at 120 feet and up off the edge of the hole in about 90 feet. It just sounded better than Target 122…

So there are some interesting questions that in my view neither the zoologists or geologists (and other unnamed interested parties) have solid answers to just yet. I must confess that my close reading of this literature is probably 5 years old so maybe something conclusive has come out but I seriously doubt it.

First off- were the Florida Middle Grounds pronounced hills in the Pleistocene or did they form from tubeworm and/or coral biomantling- literally bioherms grown by huge colonies of marine invertebrates who lived from the time of inundation (roughly 13,000 to 8,000 years ago if you look at the various color levels in the multibeam image) and when they died out because they were too deep underwater to survive? Some think they are bioherms and would not have existed in the Pleistocene.

Having been able to dive in a few places and poke into the bottom a bit I strongly suspect the FMG’s were in fact hills when this was dry land and that the biomantling of coral and tubeworms occurred on the higher points after inundation. The easiest way to test this would be a sub bottom profiler doing a test patch over the high parts. A test patch is when you drag the towfish in multiple direction to give 100% overlapping data from different angles. Then if a sediment core, up to even 30 or so, could be extracted you could see exactly what the hills are made of. A second reason I believe the Middle Grounds were hills is that in the 27meg version of the Multibeam image you can pretty clearly see what should be erosional features along what appears to be an old river channel- literally, some ancient river was channelized between the two rows of hills. Again, I am not certain I am right about this, but I sure know how we could go find out. Knowing more about why the Florida Middle Grounds are so attractive to a wide range of fish and the whole suite of organisms out there should be very useful in helping us do what we can to keep the eco-system happy.

Dead tubeworm colony in 90ft of water, top edge of The Eye of Osiris

The Middle Grounds are world renowned for the incredible fishing, as are many locations along Florida’s Gulf Coast, or at least they used to be. The loss of so much biota in the last few years from the nasty red tide blooms is devastating. Certainly sport and commercial fishing people know this and instantly feel the environmental and financial costs (among others).

There is an area of biomedical research that is taking off all over the world, especially in those hard to reach places that are not yet well explored. Within the world of Natural Products the varied environmental settings and conditions on the west coast of Florida are of great interest today. Natural Products are naturally occurring compounds or genetic structures within living organisms. When I say penicillin you should know exactly what I mean. One of the interesting ones being worked on from Florida’s west coast now is a slime (I think it was a slime) that only lives within the tissue of a specific species of Bucket Sponge that could only be studied in the lab when they finally figured out exactly how to preserve it intact after sampling.

It is not clear how many organisms have never been identified, let alone the multiples of unexamined natural compounds within them. It could be in the millions. Wholesale destruction of marine biotic communities with polluted water, or whatever we are putting out there is a very very bad idea. We are clearly starting to suffer because of conditions in the Gulf. Whether human induced or natural we better get a handle on the causes, and potential ‘cures’ for the Red Tide and the flesh eating bacteria for starters.

In 2010 I did a little bit of work off Keaton Beach, FL the day after the Macondo Prospect/Deep Water Horizon oil blowout began on April 20th. I took several vials of seawater that I’ve had in the frig since then in case anyone ever wants to take a look at them. Immediately after the blowout we noticed that the larger grouper, who were ubiquitous in previous years among the bedrock along the western shore of the PaleoSuwannee, were nowhere to be seen. In fact, there was very little moving in the water column at all. Plants and plantlike-animals seemed to be doing ok but fish especially seemed hard hit. In 2012 we were very pleased to see lots of new little fish, especially the grouper, were making a comeback. But if you think about how far we were from the oil, and Corexit they drowned it with, things had to be terrible for thousands and thousands of square miles. And this was just a blip before the red tide took over.

If you can metaphorically stand back and see the longer term processes (think Pleistocene not just the 20th Century- and even this is a very brief period in geologic time) it is clear that change is almost always the order of the day. There is no mythical point in time when everything was just right. Whatever is, is going to change. I’m starting to hear “there is a season” in the back of my head as I type this. That said, knowing that things will always continue to change should not make us think we have carte-blanche to do whatever we want to the environment.

The DeepWater oil spill was a pretty straight forward example of cause and effect: nasty stuff gets in the water and bad things happen. I suspect Red Tide and other systemic impacts are the cumulative consequence of a whole bunch of causes and are going to be that much harder to overcome because we can not stop doing the things that are hurting water and organisms that live in it. We need fresh water, we create waste water by just being humans with aah, needs, we use nitrogen rich fertilizers that get into fresh and salt water, and all manner of other sporadic and/or continual introductions of other poisons.

One way to look at this is to say that what may seem as esoteric pure research questions about what exactly happened on that Pleistocene landscape in the last 22,000 years actually provide the best information on how and why things are the way they are today. Knowing how we got here helps us understand better where exactly we are. The natural and human induced issues that concern us

I guess if there was one take away I would hope to offer is that figuring out exactly what the world was like, and is like today better transcend politics. Reality is what we are after and that should take precedence over everything else. How we go about dealing with issues, that’s politics.

Well, sorry to run so long. This did lay some groundwork for future discussions about assorted topics from when that seafloor was land with people on it, but perhaps more importantly, we (the royal we man) need to consider how little we really know about what lives out there… before we continue hurting it and lose our chance to find out, because for the moment, we dwell in ignorance.

Anybody else down here? Photo by the renowned Jennifer Adler out at Thor’s Elbow between deep dives in 2012 (just east of the Florida Middle Grounds where the Suwannee and what I think is the macro Aucilla-St Marks came together). I’m about 20 feet down making big circles, only 110 feet more to the bottom.

Strong Work. Much Appreciated.

Thank you.

Its been a couple years since this was published.

Has anyone asked about your vials of Gulf water?

When you were off Keaton Beach on the 20th, that was the day the Deepwater started gushing. That was almost 400 miles from the spill.

And the fish were already gone?

Maybe they didn’t stay around to be poisoned?

Thank you. Great read. Too bad those that should, probably will not.

Eric Johnson