N.B.- 12.11.19 Just made our first official purchase as Paleo to Pioneer for what must be a giant pdf of scanned documents from the Pratt Papers at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book Room and Library. So a big Thank You! to our first donors who have helped get us off the ground.

Realizing my last post had exposed an awful lot of un-pulled threads I started pulling. Because so many people were involved, and/or have written about it since, the primary and secondary information is widely scattered and voluminous almost beyond belief. I’ve been focusing primarily on things related to Graybeard’s demise and other aspects of this whole saga that led to another, more pleasant incident in 1877 that will be the subject of an article I am working away on furiously these days. When I have a draft submitted I will talk about it. Because only historians seem to have written about it the archaeological community appears to be totally unaware of a really important story. Will report on this as soon as I can but really need to avoid scooping myself if I hope to publish on it.

So ducking the really big find for the time being I thought I would write a bit of an update on several of the interesting topics involved. This has a couple of pleasant twists and turns along the way, up to and including the forward pass in football, really. Even this is probably a bit premature as I am getting a new book every other day or so.

As one might fear even the basic facts of this story are reported with considerable variation- including the exact number of people who left Fort Sill, OK (then Indian Territory) for Fort Marion which is not clear- 72 is the normal number presented but not always. I think this is due, primarily, to whether or not an author decided to include Medicine Water’s wife Mochi (Buffalo Calf or Buffalo Calf Woman) and any number of the additional women and children who refused to stay behind as they were part of the group but not officially prisoners of war. Because of Graybeards death (variously published as Greybeard and Gray Beard, I am using Pratt’s spelling as he is the only primary source I have from 1875) and the Cheyenne Lean Bear’s attempted suicide in Nashville probably only 70 arrived at Fort Marion on May 21, 1875.

It is clear that on April 12, 1878 64 people were freed and I have names for 8 that died, but it is not clear if anyone is unaccounted for at this point because two men were released earlier in 1877. Pratt published a list of everyone and two lists of prisoners (inexplicably dated 1874) are in the Pratt papers of the Beinecke Library at Yale and once I have those to compare to the published one it should be easy enough to figure out who exactly was held in Florida but clearly, what should be a pretty straight-forward issue, is anything but.

Somewhat harder to resolve is figuring out exactly who were the 26 younger men who drew “Ledger Art” while they were in St Augustine. Images were only drawn by Cheyenne, Kiowa, and Comanche men from the youthful end of the range. Making Medicine was the oldest artist at 31. No Comanche or Caddo men, nor the one Cheyenne lady, drew any images that are known today. I should say the 26 people are the ones who have surviving images that are known to historians and it is probable additional artists, and most certainly unknown art by known artists, exists.

In fact Heritage Auctions, Dallas, TX sold a previously unknown complete ledger of drawings only a couple of years ago. I suspect Karen Peterson listed all 26 known artists in her 1971 book, Plains Indian Art from Fort Marion, but I do not have a copy yet. If she did list them it is interesting to note that no new artists have been identified in the last 50 years. One particularly interesting aspect of the art, that leads too far afield to mention more than in passing, is the drawings are really personal rather than overtly religious or strictly culturally significant as most all of the Plains art had been prior this time. Much of it is thought to be nostalgic recollections with plenty of new experiences (shark hunting for example) depicted as well.

Having found several newspaper accounts, receiving a copy of Pratt’s unpublished manuscript about the prisoners from Yale and the slightly different version in his book Battlefield and Classroom (edited by Robert Utley, 1964 who has been very kind to me in our email exchanges), and reading at least a dozen published accounts of the Graybeard tragedy and Plains Indian incarceration, it is clear the story has more twists and turns than have been reported in any one source to date. There are a surprising number of unpublished masters thesis and PhD dissertations, usually but not always from history departments, that contain information from original sources not elsewhere published. Finding the originals then slows this all down as various libraries and historical societies are contacted.

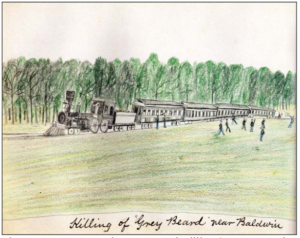

The most surprising find to me (not necessarily to anyone else who knows about these things) is that Zotom (Kiowa) made at least two different drawings of the escape and killing of Graybeard.

Image copied from page 61: Figure 3.7 Gray Beard’s (sic) Escape and Killing, by Zotom, March, 1877, in Ann Updike’s English master thesis at Miami of Ohio, 2005. She quotes Warrior Artist’s by the National Geographic Society, 1998 as her source.

So at present I am working on getting information and images from Pratt’s papers in the Beinecke Library at Yale, and need to visit the Castillo de San Marcos, St. Augustine Historical Society, and Jacksonville Historical Society. Once I have my ducks in a row from the Pratt Papers I need to query the National Anthropology Archives and regular archives at the Smithsonian.

I have hit a wall trying to get a copy of this article: The St Augustine Prisoners by Arrell M Gibson in the Red River Valley Historical Review Vol. 3 No 2? Spring 1978:259-278. Any help with that would be greatly appreciated. So there is still plenty to do and lots of fact checking remains but the two larger pieces I am working on should generate quite a bit of popular and scholarly interest.

Sorry to be so vague about my big find but to try and make up for that I thought I would leave with two final stories that are much better known but not often directly connected to what I have been rambling about. I will come back to this topic when I have more of the primary information sorted out and can present new data that has not seen the light of day for close to 150 years.

In a presentation made in 1902 Richard Henry Pratt is believed to be the first person to use the term “Racism”. He was specifically speaking about the segregation of Indians and what was wrong with that in America.

Racism first used by Pratt in 1902. Did he coin the term? Image from Wikipedia.

In 1879 a handful of the Plains Indian men that stayed east after they were released went to Carlisle, PA where Pratt was instrumental in founding the Carlisle Indian School. In 1893 later students convinced Pratt to let them have a football team. A team of small fast guys did not often fair well with other collegiate teams of the day. Smash-mouth, always run up the middle and form a rugby like pile-up with big guys was the order of the day… for a while.

On November 9, 1912 Carlisle’s on again off again coach had a number of surprises up his sleeve for their ultimate opponent. Widely considered THE GAME, for a number of good reasons, the Carlisle Indian School versus the Army (West Point USMC) football game quite literally changed how the game was played and ushered in much of the modern format. Pop Warner (yes that one) sprang trick plays, reverses, and the dreaded forward pass (which many failed to outlaw) allowing quickness to triumph over mass 27-6. I’m in the process of reading two books about this game but will end with one interesting highlight. At one point the toughest, hardest hitting Army player was injured trying to tackle the well known Carlisle phenom Jim Thorpe. Despite this setback Ike did go on to make something of himself.

The image above is excerpted from a stereoview taken very quickly after they arrived May 21, 1875. Traditional dress and hair styles have not been forcibly replaced with Army uniforms and short hair yet. Frustratingly, I have found less than 30 different Indian photographs from Fort Marion and probably less than 10 different individuals are positively identified in all of them. From the collection of the author, curated at the InterGalactic Paleo to Pioneer Headquarters by the head bottle washer.

Leave a Reply